Çarşamba continued

Sunday

On Sunday morning, March 15, 2015, I arranged to meet Laura at her and Julie's new hotel, the DoubleTree Old Town. The hotel bills itself as being nearest to the Grand Bazaar. This threw me off: it was not that near, and so I did not walk there by the most direct route from the Vezneciler Metro station. By the way, when you ascend to ground level from this station, you see the Kalenderhane Mosque right in front of you; how many locals, so used to seeing mosques, figure this is just another one of them?

Sunday was again overcast and a bit drizzly, but this was never a problem for our excursion. At a börekçi, we were told that peynirli, patatesli, and kıymalı börek were available. We sat, and I was served the cheese börek I had asked for; but then Laura was told that the börek with mince would not be out of the oven for eight minutes. It seemed to me dishonest to have withheld this information when we entered, though we could certainly chat for the necessary time, and Laura would not die of hunger. To be fair, possibly the attendant had not actually pointed to one of the börekler in the window as being kıymalı, but had said more vaguely that such would be available.

We caught a taxi to the Fethiye Mosque. Catching a taxi is something I rarely do. Our driver had not heard of our destination: he thought I wanted the Fatih mosque. I said the Fethiye Mosque was near the Selimiye Mosque. Probably I was technically incorrect here, because the mosque is properly not Selimiye, but just Selim (or Yavuz Selim, Selim the Grim, Süleyman's father). The real Selimiye Mosque is in Edirne (commissioned from Sinan by Selim II, Süleyman's son; there is apparently also a Grand Selimiye Mosque on the Asian side of Istanbul, commissioned by Selim III). When I said Selimiye, our driver thought I meant Süleymaniye. So I just got out a map and directed him. Still, near our destination, he stopped and asked a robed, bearded fellow for directions. Perhaps my own Turkish was inadequate.

Having studied the Chora book the previous day, I was not so impressed by the comparatively spare interior of the old Pammakaristos Church.

It was probably just as well then for this church to be seen first.

One sees just the side chapel or parecclesion of the old church. The word is a transliteration of the Greek παρεκκλήσιον, which is found in the Pocket Oxford Greek Dictionary, though not in the big Liddell–Scott–Jones Greek–English Lexicon, much less in the Pocket Oxford Classical Greek Dictionary. Wikipedia lists two examples of paracclesia: at Pammakaristos and Chora.

The lawn of Pammakaristos is pleasant, and in this crowded city, I am charmed by the chicken yard to the east, with the tower of the Greek high-school in the background.

We had had the museum to ourselves. As we left, a party of Turkish people considered entering, but demurred when they learned they had would have to pay five lira each (currently less than two dollars). I said the place was beautiful (güzel), but this did not change their minds. Behind this group came a foreign group; presumably they paid the price and entered.

Hirâmî Ahmed Paşa Mosque

Meanwhile, we proceeded around the corner to the Hirâmî Ahmed Paşa Mosque. You would never know it was there. On a narrow street and surrounded by buildings, it is invisible from a distance. But there it is, a little Byzantine church. As expected, it was locked, the way most mosques are in the morning.

Laura noticed that the church-mosque had no minaret, but the loudspeakers through which the call to prayer is issued were just attached to the roof. According to the printed sign for tourists, in Turkish and English, posted by the Fatih Borough Municipality in 2011, no masonry minaret was ever built, and “The wooden minaret built in 20th century [sic] does not exist today.” The sign also calls the mosque Hicami as well as Hirami. An engraved stone plaque in Turkish only, posted in 2000 by the borough mufti's office, says that the mosque was restored from ruin in 1966, having been made a mosque in 1590 by Hirâmî Ahmed Paşa himself—who is not otherwise described there, though the printed sign says he is buried at “Savak Mascid and dervish lodge.” I have a map of 115 tombs in Istanbul, but do not see Hirâmî Ahmed Paşa there.

That map, by the way, is published by the “Association for Protection and Sustentation of Tombs, Fountains, Movable and Immovable Cultural Assets” (Türbeler Çeşmeler Taşınır Taşınmaz Kültür Varlıklarını Koruma ve Yaşatma Derneği). Such cultural assets are apparently just what has been and is being destroyed, as encouraging idolatry, by the rulers of Saudi Arabia. Why revering an old book like the Quran would not be considered similarly idolatrous, I do not know.

Mehmed Ağa Mosque

I do see Mehmed Ağa on the map of tombs, at the mosque named for him (which he ordered to be built in 1585). This was near the Hirâmî Ahmed Paşa Mosque, and it was of interest to me

- for being built by my namesake Davut Ağa, and

- for its (reportedly) curious method of supporting the dome.

Studying the dome from the inside will have to wait for an afternoon, when the mosque will be open.

Tercüman Yunus Mosque

I had marked our destinations on the tomb map, this seeming to be the most convenient of the maps that I had, though it omitted many street names. After walking away from the Mehmed Ağa Mosque though, I became confused to the point of getting out my compass. This got us to the main road where we wanted to be: the road apparently called Draman, where the Sinan mosque called Drağman was to be found. Sumner-Boyd and Freely call it Drağman; but the sign on the mosque calls it Tercüman, or more fully Tercüman Yunus, that is, Interpreter (or indeed Dragoman) Jonah. When we climbed the stairs to the courtyard of the mosque, three young boys greeted us and asked where we were going. They suggested various destinations, such as the Kırmızı Kilişe or Red Church. I suspect this was the Church of St Mary of the Mongols. Mehmet the Conqueror is said to have issued a firman granting perpetual possession of that church to the Greeks. Ayşe and I had walked by it once, but it was closed then, and I had the idea that it would normally be closed. Maybe I was wrong; but in any case, for the current trip, the church was not on my itinerary. Even if it had been, we did not need boys to show us the way (even if I had just been lost).

Nonetheless, as we were leaving them, the leader of the gang (the boy with crossed arms above) held out his hand and used the only English he knew: “money money!” Now I demurred. I asked how much they wanted. “One lira” said the second in command (the boy with hood and scarf). One lira each, he specified. I did have three lira coins, which I distributed, though first I tried unsuccessfully to get the attention of a local adult, to see what he thought of the demand. Little beggars is what Laura called the boys, and I translated for them: küçük dilenciler.

But what they had asked for and received was a tenth of the cost of two tickets to the Chora Museum. Maybe it would buy them an hour or two playing video games at the internet cafe.

Kefevi Mosque

At the Kefevi Mosque (or Kefeveli, or Kefeli), the caretaker had to unlock the women's loo for Laura. Meanwhile I entered the mosque, and the caretaker accompanied me. He made sure I removed my shoes properly. Tourists do not always get this right. Shoes on stone, stocking feet on carpet: it is not hard, but some tourists go off to some convenient sitting-place to remove their shoes, and then walk on the stone in stocking feet before stepping on the carpet of the mosque. Or else they step on the carpet with shoes, since after all the carpet seems to be outside the mosque. This is a no-no. Shoes on stone, stocking feet on carpet.

The caretaker said the mosque had been the library of the daughter of Constantine. That is a bit old, if he meant the founder of the city itself in the fourth century: we were outside the city walls that this Constantine had had built. But there were ten more Byzantine emperors having the same name, the last being the last emperor of all, Constantine XI Dragases, who died in the seige led by Mehmet the Conqueror. Possibly the mosque caretaker meant one of these Constantines, or just some emperor. I did not understand his Turkish very well. When I asked if I might take photographs, he said something about how I would have to give him money for this.

What was remarkable about the mosque, aside from its not having a dome, was its two mihrabs. If I understood correctly, the mihrab in the middle of the eastern wall was for everyday use; the mihrab in the southeastern corner, for Fridays and Ramadan. But this did not make much sense. The direction of prayer never changes. The main mihrab was however confusing, since its frame was parallel with the eastern wall, making the niche itself asymmetrical, owing to the need to point more towards the south. Perhaps this asymmetry was felt to be an unacceptable distraction on especially holy days.

Meanwhile Laura had come into the mosque. As we were leaving, I asked her to give the man two lira. Use of a bathroom can cost a lira anyway. Before we could leave the garden of the mosque, the attendent called us to his little office. He dug around in a purse, pulled out some coins, and asked what they were. “Sverige Kronor” they said on them: Swedish Kronor.

“How much are they worth?” he asked.

They were worth any fortune he cared to imagine, as long as he kept the coins in his purse as he did. But I looked up the exchange rate on my mobile: the five-kronor coin was worth about a lira and a half.

Kasım Ağa Mosque

Sumner-Boyd and Freely said there were some church ruins, known locally as Odalar Camii and Kasım Ağa Mescidi, “but now virtually disappeared,” and thus “scarcely worth the trouble of finding, except for the fun of the search.” It was not clear to me why there should need to be a search. Why could the writers not just say where the ruins were? They said the ruins were on a street called Dolmuş Kuyu Sokağı (Filled Well Street); but their account of how to get to the street seemed to describe what was called Arı Sokağı (Bee Street) in the street atlas that I had consulted at home. Now that I consult another street atlas, I see that one block of this street—the block abutting the lower side of the Cistern of Aetius—is labelled as Dolmuş Kuyu Sokağı.

We wandered a bit around Arı Sokağı, I looking for such bits of old brickwork as can seemingly be found throughout the city. We found a park, and I asked a man there if he knew Odalar Camii. He may have been simple-minded though. He bade us follow him; but where he took us turned out to be the other entrance to the Kefevi Mosque compound.

I thought we might now see another extended palm, from our latest guide. But the mosque caretaker saw us and called us in. Possibly he was calling our guide instead or in addition; but the guide stayed outside. The caretaker now had another coin that he wanted identified. The lettering was Cyrillic, and the coin was 100 Kazakhstani Tenge, worth again about a lira and a half.

Leaving again the Kefevi Mosque, we chanced upon the Kasım Ağa Mosque. This had apparently been rebuilt from ruins in 1977, later than the first edition of Strolling Through Istanbul in 1972. The minaret was added in 1989.

The Cistern of Aetius

We proceeded uphill to the highest edge of the Cistern of Aetius, where we invited Julie by email to join us at the Chora Museum.

Chora Museum

We waited for Julie in the cafe opposite the museum. The museum was covered with scaffolding, ready to be covered by a canopy as the old Darüşşafaka school was.

I shall not dwell much on the former Church of the Holy Savior in Chora, since it is so well documented elsewhere. My companions were content to walk around the two narthexes of the church as I explained (from Sumner-Boyd and Freely's book) what was in the mosaics overhead. One does not need to check the floorplan in the book, since the verbal descriptions of locations are enough. Unfortunately the nave of the church was closed; but there are few mosaics inside anyway.

A question that I have not seen answered (not that I have looked hard for an answer) is: What condition were the mosaics restored from? When you look at the Deesis (δέησις “prayer”) to the right of the door to the nave for example, obviously it is not by accident that precisely the tiles around the figures or their faces are missing.

Is it possible that all of the tiles were once missing, but by clues from the impressions left in the matrix, the restorers managed to reconstruct at least the most interesting parts of the mosaics? This seems unlikely, given that the mosaics in the upper walls and vaults are often intact. My guess now is that these latter mosaics were made so high, and thus more difficult to see, in order to keep them away from prying hands, even the hands of the faithful. I suppose most tiles of the Deesis are missing because they were not so protected. At least then the faithful left the faces; but perhaps the point is that the really desirable tiles were those of the golden background. Or maybe artists themselves cannibalized the mosaic, taking the large generic tiles, but respectfully leaving the fine work of the faces. This is just my speculation.

Laura and Julie visited the adjacent shops.

I went back into the museum to take some “we were there” photos (as of the Deesis above). I thought in saying this I would be quoting Pirsig from Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance; but now that I look, I see that his words are not quite the same as mine:

At a turnout on the road we stop, take some record photographs to show we have been here and then walk to a little path that takes us out to the edge of a cliff.

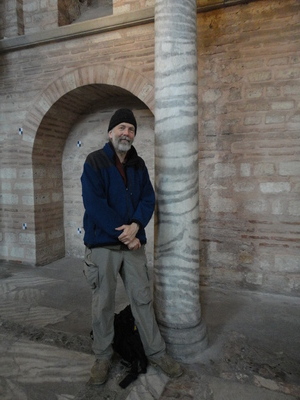

I cannot do better than somebody with a fancy camera, much less the museum guidebook; but here are the northern end of the outer narthex, the southern end of the inner narthex, and the parecclesion (on the southern side of the church). Decorated later, the parecclesion was given frescoes, apparently for being cheaper than mosaics.

The mosaics are of mythological interest for telling the story of the childhood of Mary, a story not found in the canonical gospels, but found in the Gospel of James. The mosaics give Mary stepsons, who were probably older than she was: for when she became nubile, Mary was given in marriage to that one of twelve widowers of the house of David whose proffered rod had burst forth in flower. (For the test, each widower-suitor had had to provide one long stiff cylindrical object.) It is Zacharias the Priest who gives Mary to Joseph. In Luke, Zacharias is husband of Elisabeth, who is cousin of Mary and mother of John; but this does not seem to be shown in the mosaics. We do see Elisabeth and baby John in one mosaic, hiding in a cave to avoid the Massacre of the Innocents; later, John appears as an adult, though not in the Deesis discussed above.

Here is the mosaic of the Nativity, comprising three scenes:

- Baby Jesus getting a bath,

- Baby Jesus being warmed by the breath of an ox and an ass (and getting irradiated from heaven),

- the shepherds being told of the event.

One of the keepers of a shop nearby turned out to be from Belgium, but had been living in Turkey about a year longer than I. He took Julie's email address, so as to send her the latest edition of his guide to Istanbul restaurants. He could recommend the nearby Asitane Restaurant, though not the almond soup. Ayşe had heard independently (and texted me from Ankara) that the restaurant was good, and so Laura and Julie treated me to a birthday meal there, where the dishes had supposedly been reconstructed from the archives of the Ottoman palace kitchens. Sure, the food was good, but the main point was to share a meal in good company.

Mihrimah Sultan Mosque

My companions were game for more, so we proceeded to the nearby Mihrimah Sultan Mosque—first pausing to admire yet another street animal.

Inside the mosque, a man sitting in a chair near the mihrab was addressing an audience in what seemed to be Arabic. I do not know how many Turks know Arabic that well, and so I wondered whether the audience were perhaps Syrian refugees. I did not feel like taking photographs inside.

The land walls

We walked along or near the city walls—pausing to admire cats—, down to the Golden Horn.

The tomb of Eyüp

We crossed under the highway lying just outside the walls and proceeded into Eyüp.

We caught the ferry down to the mouth of the Golden Horn.