İstanbul Laleleri // Tulips of Istanbul

18 Nisan 2015 Emirgan Korusunda 10. İstanbul Lale Festivali'ne ziyaretten // From a visit to the Tenth Istanbul Tulip Festival, held in Emirgan Wood, Emirgan, Sarıyer, Istanbul, on Saturday, April 18, 2015.

Here are photographs, with stream-of-consciousness commentary on topics like urban density, smoking, safety, global warming, nuclear power, and Ottoman Sultans.

This is our fourth spring in Istanbul, but only our first for visiting the display of tulips at Emirgan Wood. Emirgan is on the European side of the Bosphorus, at about the midpoint between the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea. Ayşe and I had been to Emirgan several times before, mainly to visit the Sabancı Museum. Most recently at the museum, we had seen exhibits of works by Joan Miró and by Anish Kapoor; the museum's permanent collection of late Ottoman expressionist paintings is also fine.

A little further up the coast from Emirgan is the picturesque harbor village of İstinye; we had been there. By bus and by boat, we had travelled as far up the Bosphorus as the Black Sea itself. But we had not climbed up to the wood above Emirgan.

For the record, according to Strolling Through Istanbul (2010) by Hilary Sumner-Boyd and John Freely, the name of İstinye descends from the Greek name Sosthenion, which is either

- a corruption of the name Leosthenion, which was derived from the name of a companion of Byzas, legendary founder of Byzantium; or

- a reference to a statue of thanksgiving erected at the village by the Argonauts.

The authors suggest that sosthenion itself is the Greek word for thanksgiving; however, according to dictionaries, thanksgiving is sostra (σῶστρα, a neuter plural). The root of this word is alluded to by the sigma in the Greek name of the Jesus fish: ΙΧΘΥΣ, standing for Ἰησοὺς Χριστός, Θεού Υἱός, Σωτήρ (Jesus Christ, of God the Son, Savior).

I shall refer to Sumner-Boyd and Freely again, for the origin of the name of Emirgan.

On Saturday, April 18, 2015, we ventured into Emirgan Wood, though from above, so to speak: we walked down from the nearest subway station.

First we had to pass the construction machinery, or rather destruction machinery, on our street in Fulya, Şişli. One of the apartment buildings on the downhill side (our side) of the street was being torn down, presumably to be replaced by a new building. I do not think any of the buildings on the street are that old; ours dates from the nineties, before the 1999 earthquake. Apparently our balcony used to be open to the north as well as the east, until the neighboring building went up. The building to our south also seems to be newer than ours. It is sad to think that not too long ago, there was still some green space around here. Now our northeastern skyline is being dominated by the skyscrapers of the Torun Center, being erected in what was open land (an athletic field) when we moved in.

One cannot tolerate living in Istanbul if one dwells too long on what might have been, like a park instead of highrises. Recently on Twitter, a Turkish expatriate in the United States shared a photo of New York City, saying it was nice, but it was not Istanbul. I am glad to share in this civic pride for Istanbul as much as I can. Istanbul does press you to make the most of it. On a sunny spring Saturday, we were going to do just this, visiting quite a bit of green space, a few subway stops away from our home station of Şişli-Mecidiyeköy.

The stop where we got off the subway was Ayazağa-İTÜ: the İTÜ here is İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi, Istanbul Technical University. Our own Mathematics Department of Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University is not on a campus, but in a highrise surrounded by a bit of concrete and a fence. Beyond the fence are the old Bomonti Beer Brewery to the north, the French Poorhouse (Fransız Fakirhanesi, operated by Catholic nuns) to the west, a bank headquarters to the east, and a new highrise going up to the south. İTÜ has a large beautiful campus—beautiful if only for having lawns and thick stands of trees within this crowded city. The plinth of a grand sundial near the campus gate provided a fine spot for a dog to doze in the sun.

Entrance to university campuses in Turkey is sometimes tightly controlled. Guards will let me into the Istanbul University campus because I can show an ID from another university. The guards at the turnstiles at the İTÜ gate did not seem to be checking IDs, though perhaps they would have stopped us if, in their eyes, we might be up to no good. Ruffians are known to visit campuses to beat up their supposed enemies—it has happened in our own university building. But at İTÜ, a couple like us could just stroll in. Thus we were able to walk a good distance towards our destination through a green landscape, rather than along a narrow sidewalk between a busy highway and a concrete wall.

In the concrete jungle where we live, the fauna is usually feline. In the more open spaces of the city, apparently, the fauna is canine. Also avian. We do see plenty of birds at home: seagulls, pigeons, carrion crows, and collared doves. The most melodious sound is the screaming of the swifts as they swoop by in formation (see my blog article). We have some house sparrows, but they do not chirp too much. On our Saturday trip to the north, we could actually hear birdsong.

One might wonder, by the way, if any songbirds that actually flew into our neighborhood would be promptly eaten by the street cats. It may be so. But then the cats are already well fed by soft-hearted neighbors, who even put carpeted boxes out on the sidewalk for the cats to sleep in. Still, the cats might indeed rob birds' nests—if we had any trees for the nests to be built in.

Leaving the İTÜ campus, we were able to continue along a quiet road, mostly residential. Some elaborate new houses were going up: single-family detached houses, not apartment blocks. I observed to Ayşe that I might be glad to have one of the houses; but then I would want to prevent any more houses from going up. In fact, on the side of the road with a view to the Bosphorus, there seemed to have been some destruction of old commercial establishments—probably cafes and restaurants—that had marred the view. One of these cafes did however remain. The group of young people who had been walking in front of us turned into it.

At the end of the road was a pedestrian entrance to Emirgan Wood. Cars were lined up outside. Some drivers were dropping off passengers; other drivers honked in frustration, although their frustration was due ultimately to their own foolishness in driving a car in this city (second most congested in the world, after Jakarta).

Family groups walked into the park carrying plastic bags full of picnic supplies. We were glad to see that making fire was forbidden. There would be no grilling of meat, no burnt offerings to the gods, if this rule was respected (as it turned out to be).

A lone yellow tulip in a bed of red ones recalled a memory. When I was growing up, my aunt had on her refrigerator a poster of a box of apples with one orange. The legend was, Be Yourself. Whether she took the message to heart in raising her own three children, I am not sure. However, she had defied her own family to marry into the dangerously radical family of her fiancé, my mother's brother. Apparently my grandfather was controversial for knowing union leaders. On his office wall at Newsweek magazine, he had pinned up a letter addressed to him in which was indited,

Whenever I read your filthy column, I am reminded of that rotten, vicious, scummy, Russian son of a bitch, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

My aunt was a smoker. Once when I was visiting her and Bill in New York, I went out to buy Jean a Times and a pack of cigarettes. The news agent was able to identify whom I was visiting by the brand of cigarette: Merit Menthol Lights. I cringe now to think of:

- the name “Merit,”

- the notion of a “light” cigarette, and

- advertisements showing active young people in bright clothing enjoying their Merit cigarettes.

Jean died of lung cancer about ten years ago, after having lived with a tank of oxygen for some time. It is true that one must die somehow. However, death by smoking seems particularly unpleasant—and unnecessary. Smoking is a pleasure, one that I have enjoyed myself in the past. But most people cannot take this pleasure only occasionally; they come to smoke habitually, as the cigarette companies desire. I would suggest that a habit as such is not a pleasure. It is however true that, was a student, the Dean of my college said he had smoked a million cigarettes in his life, and enjoyed each one (then he was diagnosed with a brain tumor, and he quit smoking).

In scolding students for smoking in university buildings, I have sometimes told them, If you are going to smoke, do not let anybody love you. My aunt is not the only person I miss who died from smoking, but who might otherwise be alive today.

Of course there will be those who point out that you can get lung cancer without smoking, or you can live to be a hundred while smoking. This is true, as it is true that winters are still cold: this does not mean there is no global warming.

Such are the thoughts brought out by flowers. Not every flower in Emirgan Wood was a tulip. The man beyond the tulips and daffodils playing ball with the girl was speaking British English. There seemed to be a number of foreigners in the park, perhaps expatriates like me, or immigrants, if you like. I do not know how many tourists with only a few days in Istanbul would make it out to Emirgan.

Posing for the camera is a common practice these days, if only because everybody has a camera on her mobile. The park had a number of spots seemingly designed for posing.

I was jealous of the children for having a spectacular place to climb. I could not even complain that the elevated rope passageway seemed to be perfectly safe. Or perhaps it was not quite safe: one might get a rope-burn from it.

Why should I complain if children are kept too safe? Usually I am sad to see jungle-gyms, even in Turkey, designed to prevent all possibility of a fall or a jump from a height. I say this without having raised children; but I do shudder to think what my own parents had to go through in raising me. Sometimes they may have been blissfully unaware of the dangers that we children exposed ourselves to, bicycling in the street, climbing trees, climbing rocks, crawling through storm sewers. While growing up, I always had scabs from bicycle accidents. I never broke a limb, though I expected it to happen, since other children got broken limbs from falling out of trees or crashing their bicycles. Are children better off now, if they never have the chance to scrape their knees? In my own childhood, I was always wearing out the knees of my pants.

Having holes in the knees of your pants is currently the hot fashion of the youth of Istanbul; but the holes are cut deliberately with scissors.

In Emirgan Wood, at least one couple were having wedding pictures taken in bowers presumably erected for this purpose.

Ayşe asked a gardener about how the tulips were planted. Apparently the bulbs came from Konya and had been planted in the fall. In a few weeks, they would be dug up and discarded. When Ayşe expressed dismay at the waste, the gardener said at least the bulbs would be composted, but Ayşe could also come take some old bulbs if she wanted. If only we had space to plant them!

There was a pond with goldfish and croaking frogs. A sign said the water was kept clean not with chemicals, but by natural biological action.

One could pose on a flowery bicycle.

Glimpses of the Bosphorus could be had here and there.

By a nice definition that I saw somewhere, kitsch is art that cheats by using subjects that are independently attractive. Since flowers are attractive in themselves, any attempt to plant them in “artistic” ways would seem to be kitsch. Thus perhaps we were surrounded by kitsch in Emirgan Korusu. This was all the more true when artificial flowers were used, as to cover giant musical symbols. Using musical symbols decoratively was already kitsch. Perhaps Istanbul has a kitschy culture, or at least the mayor does. At least the city is not at the level of Ankara, where the mayor recently erected a statue of a Transformer robot.

In any case, we have a touchy-feely culture in Turkey. I assume that the women posing arm in arm between the flowery musical notes are “just” friends.

The young woman in a pink gown and the man in a pink necktie were presumably getting engaged—not yet actually married, since the woman would wear white for this. Or possibly the couple were rebelling against the white wedding, which they perceived as foreign or otherwise undesirable; but there are elaborate celebrations of engagements in Turkey, as well as of weddings themselves.

Are there Taoists among the gardeners of the Emirgan Korusu?

There are vertical gardens on the retaining walls beside some highways in Istanbul, such as the highway to the airport.

One could have an open-buffet breakfast at a kiosk (köşk) in the park. This might be pleasant during the week, if the park is less crowded then. But I have been dismayed to see how much food is wasted by customers at an open-buffet breakfast elsewhere in Istanbul. These diners display the same mentality that makes people take a new plastic bag for everything they purchase: the bag is their right, and who knows when it might come in handy? It is just possible that filling your plate with food that you do not actually end up eating is a sign of self-control. I have seen our (female) students refuse offers of edible treats, perhaps because they are on “diets.”

Just down the hill from the kiosks was a museum, built out of the remains of the house of the Persian Emir called Güne,

who surrendered the town of Erivan to Murat IV without a battle. Emirgüne later became the Sultan's favourite in drinking and debauchery and was rewarded with a palace in this village.

Thus Hilary Sumner-Boyd and John Freely (op. cit.). In The Ottoman Centuries (1977), Patrick Balfour, Lord Kinross, dates Murat's first Asiatic campaign to 1635:

It started as a ruthless visitation of his Asiatic dominions, a bloody, inquisitorial march in which every halt saw a butchery of incompetents or suspects among his provincial officials, thronging in apprehension to kiss their Sultan's stirrup. After a solemn entry into Erzurum, between ranks of his Janissaries and sipahis, the Sultan proceeded to recapture Erivan from the Persians. His discipline was strict, but in the spirit of his forebears the troops were well provided for, his generalship won respect, and he shared all their hardships in person. He urged his generals to deeds of valour and encouraged his troops with purses of gold and silver. “Weary not, my wolves,” he would cry to them, “the time has come to spread your wings, my falcons.”

After Erivan had fallen he dispatched officials to prepare for his first victorious victory into Istanbul. He gave them also discreet orders to strangle two of his brothers…

Perhaps Emir Güne had commanded not the town of Erivan, but a town in the province of Erivan. Kinross does not mention him specifically, but says of Murat,

early in 1640 he died, after a fortnight's illness, at the age of twenty-eight. His end was hastened by debauches with drinking companions (of whom several were favored Persians)—in ironic contrast with the prohibitions he imposed on his subjects. He was troubled also by the implications of an eclipse of the sun.

Of Sultan Murat's prohibitions, Kinross says earlier,

to deprive the public of its centers of reunion and possible trouble, he closed all cafés and wineshops in the cities of the Empire—on no temporary basis but for the rest of his reign—and made the smoking of tobacco illegal. Offenders caught at night smoking a pipe, drinking coffee, or flushed with wine might instantly be hanged or impaled, and their bodies thrown out into the street as a warning to the rest.

The President of the Turkish Republic supposedly fancies himself a Sultan, as do his supporters; but which Sultan? (I might point out that Kinross's book is not scholarly. It has a bibliography of a page and a half, but no indication of how the books were used.)

Is the caftan (kaftan) on display in the museum larger than life? Not perhaps for a life of treading on carpets and reclining on sofas!

The artist on display in Emir Güne's house had incorporated Arabic calligraphy into his flower paintings. The sculpted fellow surrounded by tortoises alludes to the Tortoise Trainer, a famous painting by Osman Hamdi Bey, founder of the Istanbul Archeological Museum and of the art academy that ultimately became our university. In the painting, the tortoise trainer stands in a mosque by a window that is too low for the sky to be seen. One may infer the artist's message that religious teachers have no vision, but they impart to their pupils only their own benightedness.

In a museum exhibit about the tulip, a panel said that Murat IV brought back seven varieties of cultured tulips (yedi çeşit kültür lâlesi) from his Baghdad Campaign (Bağdat Seferi). The provided English translation called this campaign the “Baghdad Crusade.” Apparently the translator did not find “crusade” to be a loaded word.

There was a display on paper marbling. The Turkish word for this is ebru, which is also a woman's name. Museum-goers could try their hands at ebru, but only by means of a computer touch-screen.

We continued down to the Bosphorus and found a restaurant for lunch, though what we ended up eating were Turkish breakfast foods: cheeses, olives, cream and honey, and a salad of tomatoes, cucumbers, and peppers. As we sat, we could see the Bosphorus. The hoardings behind us apparently covered up the renovation of the ferry stop. Seeing our camera, a waiter offered to take our photo. He called us the happiest couple that day. Ayşe suggested that he must say that to everybody.

After our meal, we sat a while in the garden of Emirgan Mosque, built in 1781–2 (according to Sumner-Boyd and Freely) by Sultan Abdül Hamit I.

From the April, 2015, Harper's magazine, I read “Letter from Greenland: Rotten Ice,” by Gretel Ehrlich, about the catastrophic loss of ice off the Greenland coast in recent decades, a loss that prevents people from going out onto the frozen sea with dog sleds, to hunt and support themselves as they have for thousands of years.

We headed inland, back up towards the subway station. I can dream of living in Emirgan; but transportation would be a bit of a pain, whether one had a car or not. The subway is not that close, even if one gets there by walking through the campus of Istanbul Technical University.

A dog can sleep anywhere. Before photographing the dog in the gutter, I had to wait while the passenger of a passing car threw a lot of trash into a nearby bin. It is good that the bin was available, and the passenger did use it.

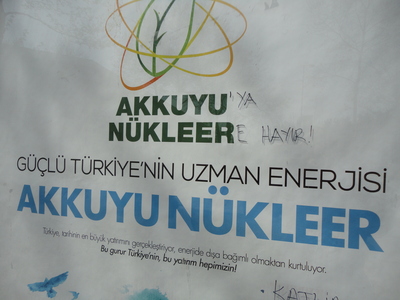

Construction of Turkey's first nuclear power plant has started on the Mediterranean (Akdeniz) coast at Akkuyu (“white well”) near Mersin. An advertising campaign is promoting the plant, on television (apparently: we don't watch) as well as on billboards. The sign on the İTÜ campus says,

Akkuyu

Nuclear

Powerful Turkey's expert energy

Akkuyu Nuclear

Turkey is realizing history's greatest investment and is being saved from dependence on external sources for energy.

This pride is Turkey's, the investment is everybody's!

But a graffitist has doctored the Akkuyu Nuclear name to read, “No to nuclear at Akkuyu!” Even the smiling fellow in the picture says no; he is an actor who thought he was being hired for the campaign of an electronics firm. He does not support nuclear power and has opened a lawsuit for having been mislead.

I talked about global warming earlier. Nuclear power will not prevent global warming, because nuclear power will not prevent the burning of fossil fuels. It will rather make those fuels cheaper, thus encouraging their consumption. Meanwhile, if even Japan was not able to prevent a disaster at one of its nuclear power plants, what hope can there be that Turkey can do so?

The hope may be in siting Turkey's nuclear plant away from the earthquake zone along the northern coast. However, another plant is planned for that coast. Turkey's is not a very safety-conscious culture. In some ways this is refreshing. I did ridicule playground equipment that had been rendered so safe as not to be much fun. But I do not think creating waste that will be dangerously radioactive for thousands of years is a good idea.

As for energy independence, the firm building the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant is Russian.

The road through the İTÜ campus now has a separate bicycle lane and a pebble garden. As far as I know, a pebble garden is not a good idea unless you want to dose it periodically with a carcinogenic herbicide like Roundup. But the garden on campus does look good now. So do the tulips of Emirgan Korusu. I am glad that Istanbul provides these few weeks of vernal agricultural titillation.